Outside of a very few specialized fields high-security locks are almost totally unknown. Even in the field of locksmithing where high-security locks are known, they are often misunderstood. Today I am going to offer you a primer on the fascinating world of high-security mechanical locks, the security benefits they offer, and what they can’t do for you.

My Introduction to High-Security Locks

When I attended my first look defeat class – a really top-notch, five-day affair – I realized how little I knew about locks. I knew almost nothing other than my key worked every day when I got home. We were learning all sorts of bypasses and defeats, and my mind almost immediately shifted to security. Just a few hours into the class I was actively wondering, “how do I protect myself from all the skills I’m learning?”

At one point during the class a student asked the instructor something that I heard as, “What about ‘medco’ locks?” The instructor indicated he knew of them and used the term “high-security locks.” Wait – what? ‘High-security’ lock? Why had I never heard of a ‘high-security’ lock? Little did I or the instructor know, but the he had just sparked an interest that would border on an obsession for the next several years: high-security mechanical locks.

I rushed home that afternoon and immediately began Googling. The student and instructor had actually been talking about Medeco locks, a very well-known brand of high-security lock. I was enthralled with the Medeco’s cleverness. Almost immediately I overpaid for a Medeco lock, just so I could play around with it. I was even more fascinated at all the other ingenious designs. Soon I was ordering really expensive and esoteric books, reading white-papers that would be mind-numbing to anyone else, scouring eBay to purchase samples of interesting high-security locks, talking to anyone who would listen…

I was – and remain – absolutely fascinated at the hugely varied and vastly superior lock designs that exist. Years later, I am even more fascinated that almost no one knows about high-security locks. There is an entire world of locks out there that vastly outclass anything found on the shelves at the big-box home improvement (or worse, department) stores, yet they are a secret from consumers. Let’s talk about high-security locks.

Defining “High-Security”

So what is a high-security lock? First, let’s define a “standard” security lock. In residential applications that is almost universally a pin-tumbler lock, usually a Kwikset, Schlage, or derivative of a Kwikset or Schlage. Most have five pins though some have six. More than you might imagine have anti-pick pins but most don’t. And that’s it – that’s what we’re up against.

So again, what is “high-security”? Turns out, “high-security” is a fairly difficult term to define. One lock can be more secure than another, but where does “security” become “high-security”? My attempts to define the term have revolved around asking first, “what do I want from a high-security lock?” The features that a high-security lock provides are more meaningful to mean than any standard or definition.

The elements that I demand from a high-security lock are: enhanced forced-entry resistance, significantly increased resistance against lockpicking, bump keys, and other forms of surreptitious entry, key control. There are multiple sub-factors under each of these categories, so let’s explore them!

Enhanced Forced-Entry Resistance

Most people who really geek out on high-security locks do so because of the novel internal mechanism that protects from forms of surreptitious entry. I certainly appreciate that and will address, but I also care about the lock’s forced-entry resistance. If you purchase a factory, high-security lock you’ll immediately be impressed by a couple things. First, it’s going to be really heavy. In my last post about deadbolts I talked about the weight of a Grade 3 vs. a Grade 1 deadbolt. Let’s take a look again:

Now let’s compare both of those to a really nice high-security lock. The lock below is an Abloy Protec deadbolt. In my humble opinion the Abloy Protec2 (NOT an affiliate link) is the crème de la crème of the high-security mechanical lock world.

The high-security Abloy deadbolt weighs almost two and a half pounds!!! That’s just shy of twice as much as the Grade 1 lock that I consider to be pretty decent. It’s almost 100 grams more than both of the other locks… added together! Also, look at that deadbolt. Looks pretty solid compared to everything else, no? Weight isn’t everything, but it is indicative of a product that is capable of withstanding more physical force than a lighter one. It also indicates some other things that I will discuss in the next section.

The second thing you’ll probably notice is that your lock comes with some really good hardware to mount on your door jamb. In my last physical security article I discussed strike boxes. Most high-security locks that you purchase from an authorized dealer will come with a steel strike box and some long screws. Installing these strike boxes usually requires a chisel and a utility knife and can take some time. I strongly recommend installing them!

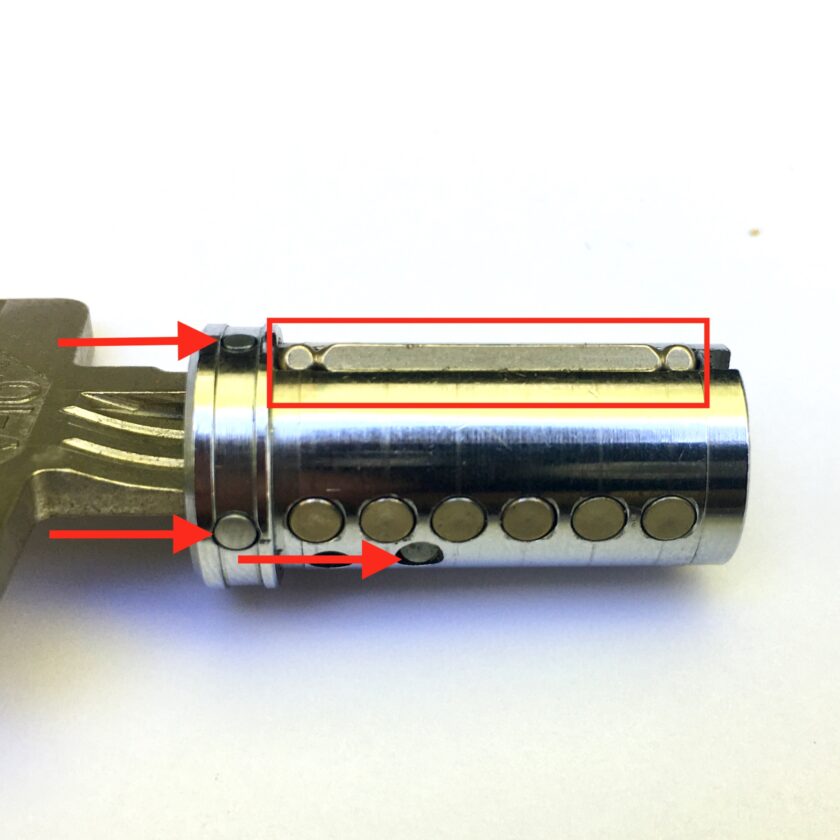

One thing you will probably not notice unless you take your lock apart (not recommended unless you really know what you’re doing) is some internal protection measures. Most high-security locks have some embedded, hardened steel inserts. These are designed to frustrate a slightly more sophisticated forced-entry technique: the drill. Most lock cylinders – even high-security lock cylinders – are made of brass. Brass is soft and very easy to drill through, so manufacturers embed hardened anti-drill pins or ball bearings into them.

The two cylinders above are from a Medeco lock (top) and a standard-duty lock. The arrows indicate anti-drill pins. These are hardened steel pins designed to break drill bits. When the bit begins to bite into the soft brass it is turning smoothly. When it catches the steel pin the tip is arrested but the shank keeps turning, shattering the bit. These don’t make the lock impenetrable but they work pretty well, and make someone spend much, much longer drilling the lock than they otherwise would. Some locks like the Corbin-Russwin Pyramid even use steel for the functioning pins of the lock.

Defense Against Surreptitious Entry

A high-security lock should also provide significantly increased resistance to lockpicking, bump keys, impressioning, and other forms of non-destructive, non-apparent entry. There are basically three ways that I see to do this: increase the tolerances and pins in a standard pin-tumbler lock, add a secondary mechanism, or develop a novel, non-pin-tumbler mechanism.

“Simple” methods of increasing surreptitious entry resistance simply improve an existing design and include adding pins and increasing tolerances. The Corbin-Russwin Pyramid is an excellent example of a lock that does both. The Pyramid is a very high-security lock that primary relies on seven pins (rather than five or six that are typical) and insanely tight tolerances. Earlier I mentioned that a heavy lock is indicative of certain factors and this is one; better materials are required to maintain such tight tolerances over hundreds of thousands of use cycles.

The Kaba Gemini (pictured above) is, in my humble opinion, an incredibly elegant and beautiful lock. It achieves its security through a standard pin-tumbler mechanism. The Gemini has a ridiculous number of pins with rows of pins coming from 12, 4, and 8 o’clock in the keyway. The pins coming from 4 and 8 o’clock are also angled, which prevents bump keys from being successful (bump keys rely on a direct transfer of force, and these change the angle of that transfer). The Gemini is one of very few pin-tumbler only locks that is well-protected against key bumping.

Locks using a standard pin-tumbler mechanism (and many other locks for that matter) will incorporate a number of other security features, including paracentric (very narrow, contoured) keyways to frustrate the use of picks and other tools, anti-pick pins, balanced pin stacks (using a longer top pin in conjunction with a shorter bottom pin and vise-versa), and others.

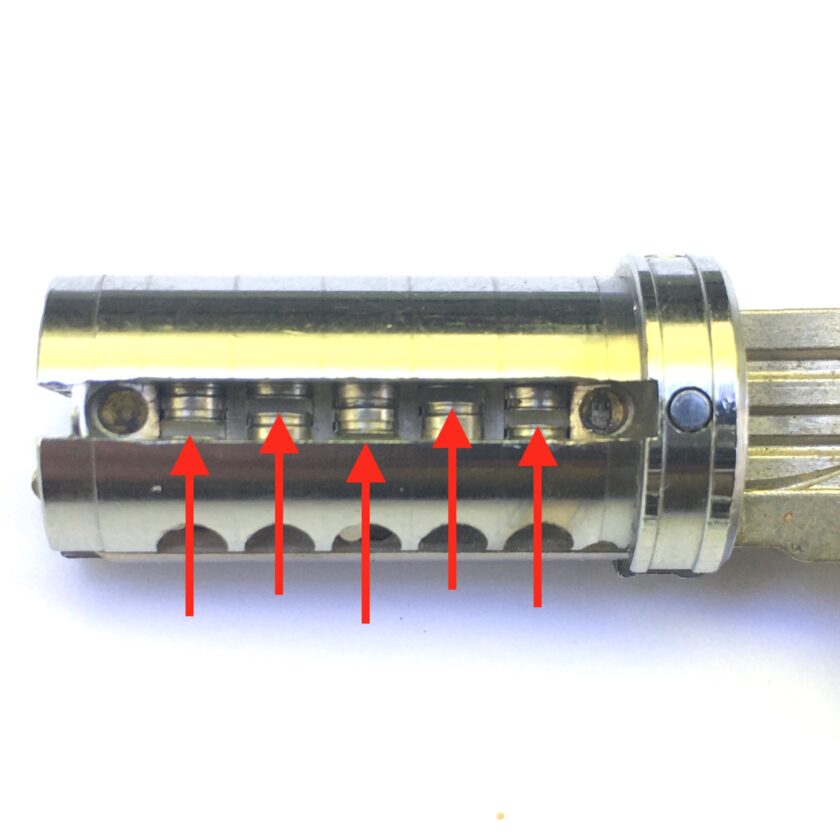

A second way locks can decrease their susceptibility to surreptitious entry techniques is by implementing a secondary mechanism. The ASSA Twin series of locks is an excellent example of this. ASSA locks are famous for their extraordinarily tight tolerances. Most are six-pin locks with anti-pick pins. The Twin series takes it a step further and also has a sidebar mechanism.

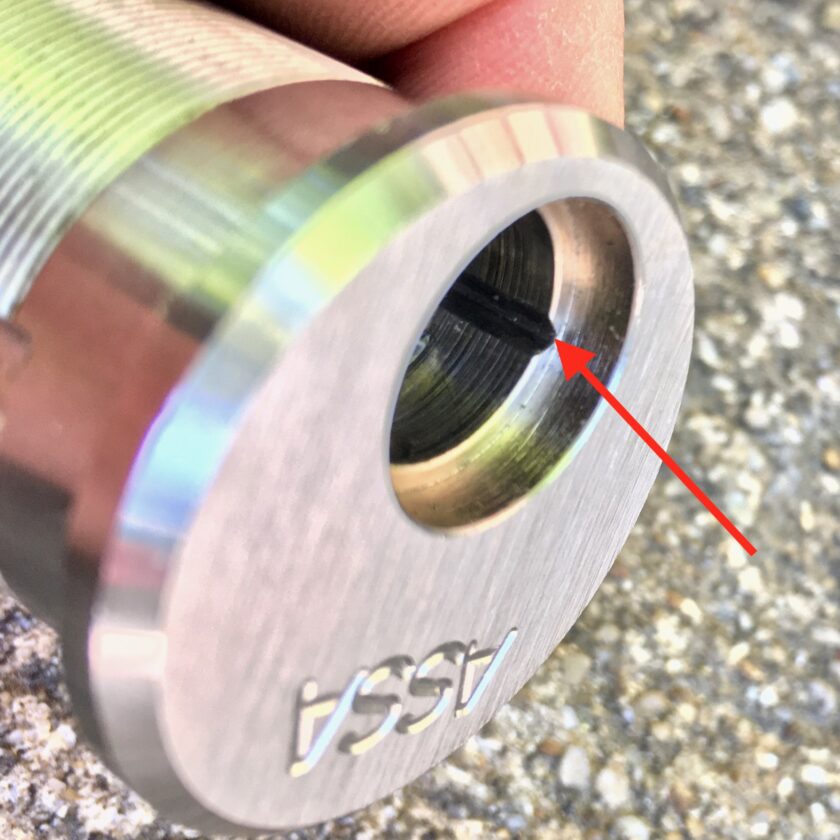

The sidebar is a metal bar that runs the length of the cylinder. When the lock is locked, the side bar locks into a recess in the shell of the lock, preventing the cylinder from turning even if all the conventional pins are raised to their correct heights.

For the cylinder to turn, the sidebar must retract into the cylinder. There are five additional pins (called finger pins) that control the sidebar. Each finger pin can be raised to one of five heights and rotated to one of two positions (fore and aft). Only when every finger pin is lifted to to the correct height and rotated to the correct orientation will the sidebar retract.

The ASSA’s key has two bittings, one of which lifts the standard pins, and one of which lifts the finger pins. To pick this lock you would have to pick six standard pins, all of which have very tight tolerances and sophisticated anti-pick features. Next, you would have to pick five finger pins to the correct height and fore/aft orientation, while maintaining the six pins you already lifted. This is a ridiculously secure lock.

The third method used to make locks less susceptible to surreptitious entry techniques is by creating a completely novel design. There are any number of designs that accomplish this. My favorite is the Abloy rotating disk system. Instead of the key lifting tumblers upon insertion, the key rotates disks when turned. Each of the 11 disks can be rotate to any of six positions, and each must be rotated to the correct position to allow a sidebar to retract and the lock to open. For a more visual explanation, go to 1:40 in this video.

Key Control

Few of you have probably given much thought to key control. I hope that my article on keys and key duplication at least got you thinking about the idea. Key control is the ease with which a key for your lock can be generated. For most of your keys I can upload a photo to a vending machine at my local department store and walk away half an hour later with a physical copy of it. Think about that for a second before you leave your keys lying on your desk at work or hand them to a valet.

One of the most important features of a high-security lock to me is prevention of key duplication. If I loan a key to my friend, I know that once he gives it back to me he has not made a copy of it. Let’s talk about how that works.

Patent protection: a huge competitive advantage in the marketplace is patent-protected keys. Companies keying large buildings want to know that their employees cannot go duplicate keys, so they go with a manufacturer who has proprietary blanks. The only entities legally possessing the correct blanks are authorized locksmiths. Of course this doesn’t completely stop black market manufacture of protected blanks but it does go a long, long way.

Locks with patented blanks that are sold to individuals usually come with some sort of key duplication card/system. When the locksmith (be it in person or an online retailer) sells you the lock they also provide you a card, similar to a credit card. When you need to have duplicate keys made you must present that key authorization card (or other appropriate information; specifics vary). Because getting blanks is difficult by non-authorized dealers, and authorized dealers may lose their ability to sell that line of locks if caught duplicating keys without requiring the proper identification, this is a pretty good system.

Security through obscurity: you also get a little bit of general security-through-obscurity with some locks/keys. Take a look at the keys below. Most of your locksmiths – to say nothing of your home improvement and department stores – will not be able to duplicate most of those keys. Most locksmiths are not going to have blanks for most of those keys because they are uncommon. Most of them require very specialized cutting machines that a locksmith may not possess and Lowe’s or Walmart definitely will not. You do gain a bit of security in that way, though I wouldn’t count on it to save me against a seriously dedicated bad guy.

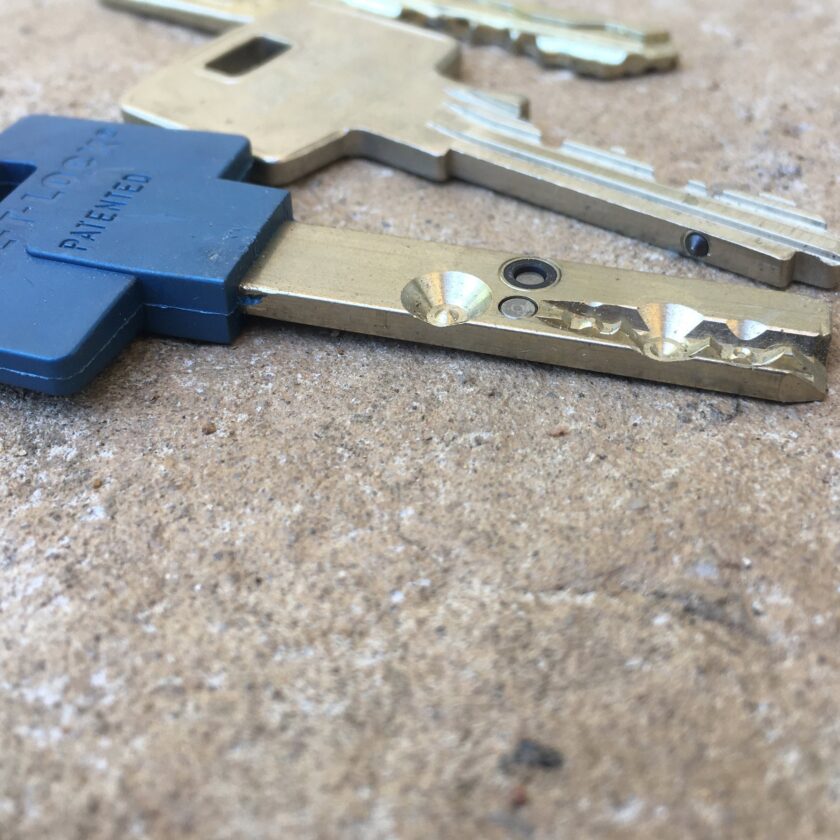

Moving elements on the key: Everything we’ve talked about so far prevents key duplication via a locksmith or retailer. Let’s look at a way to prevent less sophisticated duplication efforts. Keys to quite a few high-security locks come with a physical element that must move when the key interacts with the lock. Moving elements in the key prevent duplication of keys through things like casting a duplicate key with urethane or printing one on a 3D printer.

Pictured above is a key for the Corbin-Russwin Pyramid. Note the small protrusion on the bottom of the key (the “pyramid” from which the lock gets its name). This protrusion must slide into the key to permit the key entry into the keyway. If you create a key with this protrusion that is fixed and unable to retract, the key will not go into the keyway. Once the key is fully inserted, this protrusion must be present and it must be ejected from the key under spring tension to to activate one very small pin in the bottom of the keyway. If this protrusion is not present, that pin will to be depressed and the lock will remain locked. Could someone duplicate that? Probably, but it is very small and very precise. This simple element reduces the list of potential actors to a very, very small one.

There are other, slightly simpler systems like a moveable ball bearing present in Abloy Protec2 keys or the disks in Mul-T-Lock Interactive keys. All functionally serve the same purpose: to prevent the unauthorized manufacture of keys or key blanks.

Questions from the Audience

At this point a couple of questions will normally pop up. If someone has asked them, someone else is probably wondering about them, so I’ll go ahead and address them without being asked.

But won’t they just break a window? Yes, they might, but a high-security lock still serves a purpose for me. First, there are people who are unwilling to break glass. Breaking glass is dangerous; it is an instantly recognizable sound. Second, though not nearly as common as kick-ins, some burglars do actually use bump keys and picks. Not very many, but some. I can automatically rule them out as threats to me because they aren’t going to have a bump key that fits my lock and they damn sure aren’t going to pick it.

Thirdly and most importantly: I use high-security locks to ensure you cannot enter my home without my noticing – I want to force you to break something. If you get in without my notice, you may be lying in wait for me inside. More likely, you may have carefully come and left, and my stolen goods are days gone by the time I notice. I would much rather force you to break something. I’m either going to see it or you’re going to wake me up, and you’re going to alert the dogs who are always home.

OK – one more thing: some of you have ridiculously large televisions and owe tens of thousands of dollars on brand-new trucks. Some of you will only buy Snap-On tools. Some of you wouldn’t dream of buying an optic that didn’t cost twice as much as the gun it goes on. That’s cool – I get it. We all have our things, our areas where we demand the very best. I like and appreciate extremely high-quality locks and I’m not going to settle for pot-metal crap. I also recognize that locks are a strong, meaningful security measure that contribute directly to the safety of me and my family and again, I’m not going to settle for pot-metal crap.

Doesn’t UL-437 define high-security locks? Yes and no but…mostly no. The Underwriter’s Laboratory provides UL-437 which lists some criteria for a lock. I’m not going to go into them because I don’t think they are that important. UL-437 never uses the term “high-security” and UL-437-compliance doesn’t factor into my choices. Incidentally, though, all the locks I would recommend do meet UL-437’s standards.

Final Thoughts

Do I think that everyone needs a high-security lock? No. However, it pains me to know that the vast majority of Americans – including some with elevated security concerns – have no idea that these tools exist. There is a whole, hidden world of security that its actually kind of hard to find your way into. Hopefully this post will democratize a bit of that information. In the near future I may list some of my specific recommendations for high-security locks (if you read carefully you can probably figure out at least a couple that I like here), and where and how to buy one.

1 thought on “High-Security Mechanical Locks”

Comments are closed.