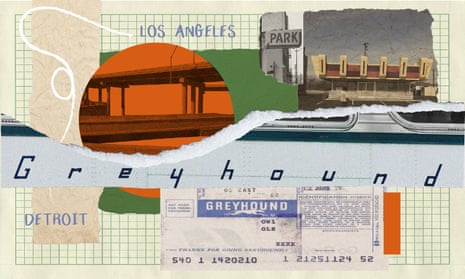

I recently completed the road trip of a lifetime. I struck out from Napanee, Ontario, to Los Angeles, California – a 2,800-mile trip that I had been planning since before Covid times. I wanted to take this time to think deeply about our overreliance on cars and our love affair with the open road.

There was a catch: as a non-driver, I would be crossing the country by Greyhound bus. It would have the advantage of getting me closer to the people I wanted to talk to, and the issues I knew I’d witness.

When I headed from Detroit towards Los Angeles, I knew I would encounter ecological catastrophe. I expected the poisoning of rivers, the desecration of desert ecosystems and feedlots heaving with antibiotic-infused cattle.

What I found was more complex, nuanced and intimate.

Historically, chroniclers of the road have travelled by car – intrepid individuals in charge of their destinies. They also tend to be male. The only book I could find by a woman about crossing the US was America Day by Day by Simone de Beauvoir. It is also the only Great American Road Trip book that features Greyhound bus travel. Simone became my companion on the road.

My first stop was Detroit. I was unable to find a clean, cheap hotel in the centre of town. My only option was to download an app by Sonder, which offered affordable Airbnb-style apartments with kitchens (thus saving me money on food). I handed over my debit card details to this San Francisco-based hospitality company and received a code with instructions to a room in a faceless building. I would not meet another human during my stay.

This atomisation, and the reliance on tech for our most basic human needs, unnerved me. It became a leitmotif during my trip, and also spoke to something I saw repeatedly: the exclusion of those without smartphones or credit cards. The cashless society appears to be winning.

From Detroit, I headed to St Louis, via Columbus, Ohio, where the Greyhound would hit Route 66. My 20-minute stopover in Columbus was where a picture began to form of what Greyhound travel looks like today. The bus station consisted of a parking garage the size of a small airplane hangar. At both ends, electric doors opened and closed when a bus entered or exited. Between the two bus lanes sat a small concrete island where passengers were disgorged. There was a chemical toilet, no drinking fountain, very few seats and no windows. The air was choked with exhaust. A police van was parked at one end of the tunnel and armed policemen stood against a wall facing us.

If you had commissioned an urban planner to design the most hostile, uncomfortable and unhealthy environment for passengers, this would be the result. I guess this is what you get when you travel in a seat costing $35 as opposed to a $200 plane ticket or in a car with a full tank of gas.

My next bus was scheduled to leave for St Louis – a mere 530-mile trip – at 3.00pm. I looked around at my fellow island-dwellers: an elderly man with four large zip-up bags printed with “Patient Belongings”; a couple travelling with a large fluffy blanket propped up against the Porta-Potti as a makeshift bed; a mother and her teenage son carrying large cardboard boxes. The sign on the empty Greyhound kiosk read: “As of 25 January 2023 – you will need photo ID to buy tickets.” Yet another barrier between those with little money, no fixed address, no car, no passport or credit card and their ability to travel.

Five pm and still no bus. Another passenger, a university student from India, had been checking his app, which showed that the bus had been and gone. How could we have missed it when we hadn’t left our island? Ruben, a young Amish man, approached. I gave him my phone so he could tell his family he would be late. A one-handed man asked us if we knew what was going on. We didn’t, so he told us his story: he had lost his wife and daughter recently and had just emerged from a 14-month coma – the result of being electrocuted at work, which also saw his hand melt. Like so many of the people I met on the road he had suffered extreme anguish, but had found God. “I am now never alone,” he told me.

The four of us were discussing tactics when a Greyhound employee showed up. Desperate passengers trying to get to bedsides, parole hearings, jobs and loved ones swamped her. She looked utterly out of her depth.

Our bus showed up, but we were further delayed while passengers on it waited for their luggage. Apparently, its faulty hold had opened and bags had scattered along the highway – or so the story went. You never quite know on a Greyhound. The rides can take on a mythical dimension. Our driver had never done the Columbus–St Louis route before and we wound our way through unlit back roads until a marine on board snapped and ordered her to use his GPS.

At Indianapolis, the driver – shaken and angry – quit. A replacement was found, and we got into St Louis as the sun was rising. An eight-hour trip had stretched into 24.

My motel in St Louis was a run-down Americas Best Value Inn & Suites wedged between Interstate 44 and the Mississippi River. It was the cheapest motel I could find; there were conferences and ball games in town which meant prices had been jacked up. My filthy, dark room set me back $180 (and another “accidental” $415 taken from my debit card which took weeks to sort out).

After a sleepless night worrying about bedbugs, I got to the bus station at 6.00am. Several buses had been cancelled and the station was heaving. The vibe was nervy and angry. Miraculously, a coffee counter was open. In most stations, the diners are closed and the vending machines border on empty. I ordered a bagel with cream cheese as a skinny man with eyes the size of silver dollars started yelling about a lost cellphone which had his ticket on it.

The security guard, a tall trans woman with bright nail polish, calmly walked over to him. The guy next to me at the coffee counter nudged my arm and pointed: “Her revolver is the same as my grandad’s,” he laughed. “It’s old. Probably doesn’t even work.” The man was now pounding the wall while the security guard kept one hand on her holster.

We could relate to the screaming man – somewhat. “The problem is, it’s all digital now. They just look at their computer,” the guy said, miming someone typing officiously on a keyboard. “‘Sorry I can’t help you,’ they say if it’s not right there on their screen. Nobody cares.”

The combination of cancelled buses, a customer care phone line that is impossible to penetrate, an online system that can’t track bus routes accurately, and exasperated and unsupported Greyhound staff leads to desperation for travellers. Even for those with smartphones who can download the app, the information on it is often wrong.

From St Louis to Albuquerque, I had over 1,000 miles to cover. I had planned to read, but none of the overhead lights worked. Many of the buses are slowly falling apart.

The company has been struggling for a while thanks to cheap flights and a pandemic which reframed close quarters with strangers as a potential death trap. Greyhound was bought in 2021 by the German-owned FlixBus. They don’t own the physical stations, however, and are fast becoming another Uber-style company, connecting consumers online with a service. One of my bus stops consisted of coordinates along a four-lane road.

Simone de Beauvoir’s descriptions of riding the Greyhound are unrecognisable: “I read, I look, and it’s a pleasure to give myself over from morning to night to a long novel while the landscape slowly unfolds on the other side of the window.” The quaintness Beauvoir describes in 1947 sounds wonderful, but on another level her journey was marred by injustice. In the early 1960s, Greyhound buses were used by the Congress of Racial Equality for their Freedom Rides. Members rode through the south to ensure stations were complying with the US supreme court rulings to allow Black and white people to mix – sometimes leading to violence against the freedom riders.

None of this oppression is touched upon in the literature of the Great American Road Trip, because in your car you are removed from the communal, from the people who, behind the scenes, are keeping much of the country going: the cleaners, care workers, manual labourers and those doing necessary work – with little fanfare and often for very little money.

As you approach Albuquerque, just beyond the 100th longitudinal meridian – the dividing line between east and west – the light changes, the horizon retreats, the emerald greens turn minty, and your heart opens a little. At the Texas panhandle, the ground takes on a deep red hue, and by the time you reach New Mexico, the colours have become psychedelic. You’ve arrived in the west.

My hotel in Albuquerque was an Econo Lodge on Central Avenue (AKA Route 66), tucked under the I-25. A five-minute walk from my front door was what I took to be an abandoned motel. As I took some photos, a guy in a pickup rolled up. “Are you looking for Jesse?” he asked. Not being a Breaking Bad fan, I didn’t get the connection. Pickup guy was the owner of the Crossroads Motel. “This is where Jesse stayed,” he said. If buildings could be method actors, the Crossroads would win an Oscar, with the glowing pink Sandia Mountains and golden light in supporting roles. As with most of my stops, I only allowed myself a night in Albuquerque, but I had wished for more. I never like leaving New Mexico. Simone de Beauvoir called it the “Land of Dreams”, a place that made her “muse about the mysterious marriage binding our species to this planet”.

The only direct Greyhound bus you can book from Albuquerque to Vegas takes a minimum of 21 hours and does a bizarre route via San Bernardino. This is where you have to get creative. I worked out that if I went to Phoenix and changed there, I could do the trip in less than 18 hours.

I decided to walk to Albuquerque’s bus station early as I was tired of lugging my backpack around. A city bus honked and pulled up next to me. The driver motioned for me to get on rather than walk alone in the dark. What I didn’t know was that Greyhound stations now often close between buses to keep homeless people out – yet another communal space closed to those without the money to access private spaces. Dozens sat on the steps of the station shivering; some were lying in the foetal position; others hopped from foot to foot like their feet were on fire. I gave what food I had to anyone who wanted it, but I still had an hour before my bus.

I remembered Beauvoir’s descriptions of bus stations with restaurants, juke boxes, showers and lockers she compares to columbariums. Columbariums! I walked to a cafe where I very slowly nursed a cup of chamomile tea as part of my near-dehydration diet which had managed so far to keep me from having to use a bathroom on the bus.

I was arriving in Las Vegas on a Thursday, when the prices rise, so I booked the cheapest off-Strip motel I could find. As the bus approached town, I decided to read the reviews: “Filthy hotel … Wish I would have read reviews before I went to this dump.” Stained sheets and gunshots were mentioned. I panicked and texted a writer friend in Vegas who told me about the HotelTonight app. Once again, I succumbed to the appification of travel, which saw me bag a room at the Tropicana for $50 – far less than the price of my now-cancelled room at the Wyndham Super 8.

In 2021, Vegas’s Greyhound station at the Plaza Hotel moved 10 miles south of the city’s downtown. With its xeriscaped native plants, the building is a glass and steel model of a functional civic space – albeit one removed from the centre of the city. After two nights in Vegas, I filed on to the Los Angeles-bound bus for the final leg of my trip, and watched a ticketless young woman with very swollen ankles beg the driver to take her out of town. We pulled away, leaving her crying quietly on a bench. The city disappeared behind concrete highways, eventually giving way to a vast desert draped in a strawberry-coloured dawn.

When Beauvoir first arrived in the US, she wrote about seeing “all of America on the horizon. As for me, I no longer exist. There. I understand what I’ve come to find – this plenitude that we rarely feel except in childhood or in early youth, when we’re utterly absorbed by something outside ourselves … in a flash I’m free from the cares of that tedious enterprise I call my life.”

That sense of no longer existing flourishes on the road. That sense of escaping the enterprise we call “our life” – that is the pull. Although, for many, their journey is their life. What I found on this trip was a changed landscape: gone are the small, clean, cheap motels in the centre of cities, gone are public spaces where anyone can find a water fountain, a bathroom, a place to nurse a cheap cup of coffee and human company. And yet the camaraderie on the Greyhound is just about hanging on – but I wonder for how long?

When you find yourself gazing at the horizon as the sun rises, each little sage bush with its purple shadow stretching into a seemingly infinite sandy blur, a quiet descends. Everyone feels the power of these landscapes. Maybe that’s what’s unique about road tripping by Greyhound. There are other places we think we’d rather be, but here we are in the moment, trundling along all of us together looking out at the same earth, breathing the same air, all of us knowing deep down that where we are really is where we’d like to be.

There is no app for this feeling and, thankfully, there never will be.