When George Saunders went out to his writing shed to start a Substack newsletter last fall, for the first time in a long time, the Booker Prize-winning novelist, famous for such works as Lincoln in the Bardo and Tenth of December, didn’t know what he was doing. “I’ll just write 80 posts and then take a vacation,” he thought to himself. But upon hitting publish, something surprised him: the comments section exploded, with thousands of readers chiming in on his inaugural post (that still-growing comment count currently sits at 3091). Everywhere from Scotland to India to Australia, devoted followers and aspiring writers wrote in with passionate messages, eager to connect with one of their literary heroes. Suddenly “don’t read the comments,” that old digital age chestnut, felt like the worst advice in the world. There was nowhere else Saunders would rather be than here, chopping it up with commenters young and old, near and far, longtime fans and first-time callers.

“The fun of it has been reading the comments,” Saunders says. “People are so honest, earnest, and heartfelt. Somebody will confess to having a certain blockage, and it’s hard for me not to respond to their comment, or come up with a writing exercise to help them. That’s going to be the thing that allows me to keep doing this for a long time, just getting in there and mixing it up wherever people are.”

The comments section is a modern invention, but it stands to solve a longstanding problem for the literary world. Great novels make us feel changed, seen, spoken to. But when readers want to continue the conversation, how can they speak back? For most of literary history, the only answer was to enter a lopsided pen pal program with your favorite novelists by sending letters care of their publishers. The advent of social media brought readers and writers into closer contact than ever before, but increasingly, an author’s social presence is just another thing to manage and manicure, rather than a freewheeling real-time discourse with readers. What if you could hear from your favorite novelists on a regular schedule—essentially, enter the slipstream of their minds on demand? Enter Substack. A small but significant cadre of novelists are migrating to the publishing platform best known as a newsletter distribution tool for journalists. There, titans of contemporary literature like Saunders, Salman Rushdie, and Chuck Palahniuk are serializing fiction, teaching the craft of writing, and yes, believe it or not, wading into the comments section. Many months into the experiment, they’ve amassed thousands of subscribers, deepened their dialogue with readers, and built the digital enclaves we all dream of: positive, vibrant, teeming with good faith discourse. But as these novelists light the way for what a safe, congenial online community can look like, they raise questions about their beleaguered platform, and about what it will take to build the digital world we all want to live in.

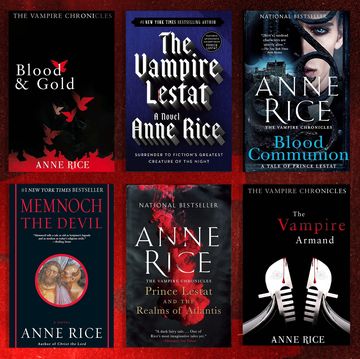

The first marquee novelist to strike out on Substack was Rushdie, who started his newsletter, Salman’s Sea of Stories, last September. “The point of doing this is to have a closer relationship with readers, to speak freely, without any intermediaries or gatekeepers,” Rushdie wrote in his inaugural missive. “There’s just us here, just you and me, and we can take this wherever it goes.” Since then, it’s gone to myriad places, from serialized chapters of a new novella to “ask me anything” posts to Rushdie’s pan of Dune. Then, later that same month, Palahniuk joined the fray with another similarly roving enterprise: Plot Spoiler, which hosts serialized chapters of his latest novel, called Greener Pastures, lessons on the craft of fiction (complete with homework assignments), and charming snapshots of his Boston terrier. Saunders rounded out the picture in December with Story Club, an “interactive, challenging, and rigorous” series of guided readings, writing exercises, and notes of encouragement for aspiring writers, almost like a budget MFA program. Each of these newsletters, though free to sample, ultimately run subscribers $6 per month.

What’s tempting some of today’s most decorated novelists to hang out their shingles on the world wide web, you might wonder? As with any literary venture, there’s an economic proposition. These newsletters may very well fall under the auspices of Substack Pro, a specialized program that offers select high-profile writers an advance payment to subsidize their first year on Substack in exchange for 85% of their subscription revenue; after the first year, these writers no longer receive a lump sum, but collect 90% of their subscription revenue. Because Substack doesn’t disclose the list of writers with whom they’ve struck Substack Pro deals (much to the consternation of its critics), Esquire can’t confirm the nature of these writers’ arrangements with Substack, though key details suggest that they’ve indeed inked these lucrative deals. Palahniuk has disclosed that his advance from Substack is comparable to the advance he’d otherwise receive from a traditional publishing house, meaning that his migration to Substack is virtually risk-free, with guaranteed income and only a one year minimum commitment. Though Rushdie’s Substack advance falls short of what he could expect from a traditional book advance, the technology lends itself to his desire to write discursively on everything from photography to French New Wave cinema—and to do it “without mediators or gatekeepers.” A Substack Pro deal also comes with access to legal resources and a modest healthcare stipend; Palahniuk made mention of the latter during our conversation, noting that although he purchases health insurance elsewhere, he believes that, in offering subsidized healthcare, Substack has addressed “the biggest issue for independent freelance writers.”

If it sounds like a cushy arrangement for novelists working in the notoriously low-earning literary fiction space, that’s because it is, but just who gets one of these covetable arrangements? According to Sophia Efthimiatou, who leads Substack’s writer recruiting efforts, it’s a complicated calculus. “When Substack first started, it was best known as a tool for journalists,” she says. “Part of our job is to introduce this sophisticated tool to writers that may not think about it as an option for them. Writers approach us with ideas, or we approach writers for whom we think Substack would work well. What do they want to do on Substack? What are they looking for? We go after who we think is going to do very well.”

But just which novelists do they consider safe bets? Mark McGurl, a Stanford University professor of literature and the author of Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon, has spent years researching the influence of digital platforms on literary life; he notes the perhaps obvious idea that the Substack model trends toward novelists with an existing readership. “For somebody who’s not well-known, it would be pretty tough to go from zero to enough paid subscribers,” McGurl says. “It's mostly a way of leveraging the popularity that someone already has.”

There are a great many successful novelists from a variety of backgrounds—and yet, of the countless high-profile novelists Substack could recruit to the platform, their current bench is disproportionately weighted toward men. Notably, when Substack launched a media campaign for its literary programming in late 2021, they didn’t have a single high-profile female novelist to their name; today, that still remains true. Efthimiatou argues that this literary push is still an emerging endeavor, with plans to grow and diversify. “We’re talking with many writers and agents,” she says. “It has to do with finding the right moment to start something with them.” Efthimiatou notes that publishing houses are interested too, and are cold-calling Substack to inquire about onboarding their writers to the platform.

Although the literary program has room to expand, it won’t be a fit for every novelist with an established readership. “The model definitely favors writers who are extremely gregarious and prolific, and who have highly identifiable, bright, colorful writing styles,” McGurl says. “It's harder to imagine a more tortured writer—the ones who come out with very little work, in small doses, because they’re suffering for every word they get down. It's hard to imagine them in this medium, because the pace is ultimately journalistic. You're almost like a columnist.” But for novelists with the right constitution, there’s a lot to love about the experiment. For Palahniuk, Plot Spoiler offers a sustained connection with faithful readers, many of whom are located in rural or international markets where traditional publishers haven’t shipped him on book tour. “It’s such a joy to interact with people on a regular basis,” he says. “When I go on tour, at the most I've got two minutes with each person in line. But with Substack, I'm talking to the same people almost every day, every week. It’s given me a deeper experience of my readers.”

For Saunders, who’s recently scaled back his course load at Syracuse University’s graduate creative writing program (where he’s taught since 1997), Story Club functions as “a surrogate teaching experience,” as well as a democratization of a characteristically rarefied creative writing education (after all, $6 per month is a lot cheaper than Syracuse tuition). “It feels a lot like an MFA program, but suddenly you can open the door and say, ‘Everybody come in,’” Saunders says. That devotion to the project cuts both ways, if the enthusiastic audience response is anything to judge by. “I signed up for George Saunders’ Substack on short story writing but I fell behind and now I’m so worried about disappointing him it’s stressing me out,” tweeted television writer Lila Byock.

A Substack newsletter also offers these novelists some of the most prized commodities of a creative life: time, autonomy, and flexibility. Saunders prepares his newsletters on Thursdays and Fridays, shares with a freelance editor over the weekend, then posts to Story Club the following week. It’s a schedule that more or less mirrors his experiences as a professor; “I put it in the slot where teaching normally would be,” he says. When Palahniuk joined Substack, he found himself thinking about Plot Spoiler “night and day,” constantly brainstorming ideas for posts and hunting down artwork to accompany them. But a few months into the experiment, that balance has leveled out, as part of Palahniuk’s attention has returned to working on a new novel (one he’s not serializing on Substack). These newsletters also offer complete creative control; although resources like editors and graphic designers are available, novelists needn’t take advantage of their services, and can build something free of editorial oversight. “The idea that I would not be heavily edited was part of the appeal,” Palahniuk says.

But just how truly trailblazing is this set-up? The autonomy of Substack offers novelists greater control than ever before over serialization, which has historically been brokered through publications and periodicals. While classics like Madame Bovary, Heart of Darkness, and War and Peace had to depend on the favor of newspaper and magazine editors to reach their audiences, the next Great American Novel could find its footing on Substack, no pesky gatekeepers required. But reaching readers by email newsletter, McGurl notes, is an old trick from the toolbag of self-published authors, who have long cultivated their readership by email. “Parts of this are new, but mainly as a way of aggregating and making more efficient things that have existed in other forms before,” McGurl says.

What’s truly novel about Substack’s literary experiment, then, is what it signifies about the changing nature of authorship. In the age of social media, authors have long been expected to brand themselves, packaging their livelihoods into a marketable identity distributed across social platforms, websites, and live events. Now, as novelists embrace Substack, they’re leveraging their brands not just into a new platform, but a new distribution model: consistent points of contact, delivered into readers’ inboxes at a regular frequency, with the added intimacy of a discursive, freewheeling comments section.

McGurl calls it “authorship as a service,” because financially speaking, it’s not dissimilar from how software is increasingly sold as a subscription, rather than as a one-time purchase. “We live in a world of ‘as a service,’ and Substack is beginning to converge with that,” he says. “You go to Substack and get your dose of an author. If you've got subscribers, they're subscribing to your work. You don't have to rely on them seeing a book review, realizing that your new book is out, and maybe buying it. They've already bought into you.”

As promising as business may seem in these novelists’ corners of Substack, trouble is brewing elsewhere on the platform. Substack has long faced criticism for its desire to act solely as a platform, meaning that it provides a technology and then adopts a hands-off approach, rather than as a publisher, meaning that the company is accountable for the results of its financial and editorial decisions. It’s a fight we’ve seen play out time and time again with other embattled tech behemoths—like Facebook, which has shirked its moral and legal responsibilities by arguing that it’s simply a neutral platform, and Spotify, which recently faced widespread backlash when it refused to curb podcaster Joe Rogan for airing anti-vaccine misinformation.

The saga continued in March 2021, when Substack came under fire for reportedly paying undisclosed advances to transphobic writers under the auspices of its Substack Pro program; critics urged the company to identify which writers are a part of Substack Pro, but Substack declined to provide that transparency. Tensions have once again reached a boiling point following a January report from the Center for Countering Digital Hate, which calculated that anti-vaccine misinformation on Substack generates at least $2.5 million in annual revenue. When urged to curb misinformation by adopting a more stringent content moderation policy, the founders of Substack equated moderation to censorship. The ongoing controversy has the potential to stop Substack’s literary expansion dead in its tracks. As Elise Thomas, an analyst at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (a UK extremism think tank), wrote, “If Substack becomes known as a platform for anti-vaxxers, conspiracy theorists and the far-right, it will be difficult to attract the kind of credible, high profile writers which Substack has been courting.”

These high-profile novelists, for their part, see their endeavors as isolated from Substack writ large. Saunders described Story Club as “my own little fiefdom,” separate from the more politicized discourse, while Palahniuk confessed that he doesn’t read much of the polarizing opinion writing on Substack. “If somebody can teach me something, I'd love to be taught, but I'm just burned out on hearing people's opinions,” he says. “I don't care anymore.”

In these little fiefdoms, novelists offer an instructive roadmap for what content moderation can look like. Efthimiatou notes that writers have “absolute control” over the rules of conduct in their growing communities, with the power to prevent disruptive users from commenting; they can also report troublemakers to Substack administrators. “It's their publication, and they define the rules of how people should interact,” she says. “If they're not comfortable with something, then they have the power to remove it.” Of the thousands of commenters at Story Club, only a handful have caused problems, but Saunders takes the task of setting the tone seriously. He compares his role as moderator to his role as professor, saying, “I try to interact with people as if they were my students. In class, if one student started calling another student insulting names, I would stop that shit right away. You get out in the hall.”

It’s a compelling thought experiment: what if we treat the social Internet like a writing workshop? At their very best, writing workshops operate under rigorous codes of conduct, disallowing harassment, encouraging inclusivity, and fostering community around a shared creative experience. “In class, the subtext of a workshop is to instruct people in how to most profitably workshop something,” Saunders explained. “What language do you use? Can you train yourself to be really specific in your critiques, and therefore not personal or hurtful? I want to teach the application of specificity. Weirdly, that ends up being a practice of congeniality. The more specific you can be about a work of fiction, the less personal stuff you bring to it—the less judgment, the less snark.”

Palahniuk also takes community moderation seriously, particularly when it comes to the fiction showcased on Plot Spoiler. On both his own serialized chapters of Greener Pastures and the student work he’s shared with his audience, he’s disabled comments entirely. “I really don't want my students to be subjected to any kind of unpleasantness,” he says. “God bless the comments. I love interacting in all the nonfiction portions, but I just don't see them as useful in the fiction portions.”

Whether the remedy is cultivating the tone in real time or cutting trolls off at the knees, it all begs the question: can the Internet learn to play nice? Saunders sure thinks so. “If we assume the best of other people and adopt some kind of method for enforcing that, then I think people enjoy manifesting positively with one another,” he says. “I know I do.”

The method is paying off with subscribers, who are taking advantage of these mediated spaces to form meaningful bonds not just with their literary hosts, but with one another. In the comments sections of Plot Spoiler and Story Club, subscribers crack jokes and swap book recommendations; they bond over everything from ballroom dance to shared writer’s block. Fiction and its craft may be the milieu, but the connections run broader and deeper, offering a glimpse at just what richness can come of a few sensible guardrails. “There were a lot of comments early on about how Story Club feels like a safer place than the Internet,” Saunders says. “It’s made me think quite a bit about contemporary discourse, and about how the unspoken rules of the Internet are not necessarily good rules. We make our own rules, and the way we choose to talk to one another defines our culture. We enter into this place where suddenly I can say anything I want to you if it's not in person. I don't know if this has ever been the case in human history. Story Club seems to me like a pretty fun, virtuous experiment to see how big a positive community we can make.”

Substack has created a compelling case for novelists to come aboard, but the jury is still out on whether it’s compelling enough to stay. Substack writers retain the copyrights to their newsletters, empowering novelists to later publish their essays and serials in a more conventional physical form. Palahniuk, for his part, is open to the idea of publishing Greener Pastures with a traditional publisher, though he intends to add ancillary material to ensure that readers aren’t paying twice for the same product. Notably, Palahniuk originally intended to publish Greener Pastures with Hachette; the publisher allowed him to take it back in exchange for a different novel, set for delivery later this year. Just how radical or disruptive can Substack’s literary expansion be when writers can walk after a year, take the material with them, and publish it with traditional publishers? McGurl, for his part, isn’t certain that the experiment will scale. “I'm quite sure that plenty of fiction writers won’t be interested,” he says. “Like everything on the Internet, there has to be new content, or it's going to die. If you're trying to write your next novel simultaneously, Substack could compete with that project. I think this will remain a relatively small-scale phenomenon, though it has potential for a certain kind of writer.”

As for the small corpus of novelists already on Substack, the future is uncertain. “I don’t want to be [Substack’s] cheerleader,” Rushdie told The Guardian. “It was interesting for me to have a go with this, and all I’ve done is make a twelve month commitment. A year from now, I’m going to see where we stand, and I’ll either go on with it, or I won’t.”

Whether these novelists stay or go, whether more join up or not, we’ve glimpsed one possible digital future. The more perfect Internet we all dream of—one free of misinformation and abuse, one rich in community and meaningful connection—is a reality on these novelists’ Substacks. It can be a reality elsewhere on the Internet, if we want it badly enough, and if we’re willing to make the changes it’ll take. If you’ve got six dollars to spare, you can start the work now.