On keeping the "uppy" in "puppy"

2023-11-07

Dear friend,

“Your dog out-ranks you by one,” said Corporal Dave Robinson at Sunday’s Vets Town Hall at Brattleboro’s American Legion. I looked this up later—all military service dogs are considered NCO, or non-commissioned officers. They are given a rank higher than their handler to encourage respect, and to ensure that any mistreatment will be harshly punished.

Robinson went into Army K-9 training after 10 months on active duty in Haiti during Operation Uphold Democracy in 1994–1995. To hear him describe what he had to do in Haiti and how it made him feel, the bond he developed with dogs gave Dave a new start on life. He served another five years in K-9 operations and his best friend is Otter, his current pooch.

Robinson enthused about the capability of a healthy, well-trained dog. “I trusted it,” he said.

Corporal Dave Robinson with Otter

“Maybe dogs have it right altogether with living in a pack,” Dave told me, one of several items he listed off on what we can learn from dogs.

***

Not all of what we learn from dogs comes from healthy animals, unfortunately. There’s another canine story I’ve been wanting to tell in this space. Please skip it if you don’t want to read about abusive animal experiments.

What can we learn from the lab of Martin Seligman, Ph.D. in 1967?

Psychologists have long studied how animals learn new behaviors. But as he explained in his 1972 paper, “Learned Helplessness,” Seligman noticed that these experiments lacked real-life applicability in one critical way.

In countless experiments on mice, for example, experimenters teach behavior by reward (“positive reinforcement”), or by punishment (“negative reinforcement”). If the mouse solved the puzzle, it got the treat or avoided the electric shock.

“Nature, however, is not always so benign in its arrangement of the contingencies,” explained Seligman. “Not only do we face events that we can control by our actions, but we also face many events about which we can do nothing at all.”

In other words, while the mice controlled their own destiny in every experiment, Seligman recognized that people are often traumatized by events outside of their control. What leads some people to respond with more resilience than others?

Seligman’s lab started by running a more typical lab experiment on the control group. These dogs were placed in a room where researchers delivered them a painful electric shock via the floor. They howled, urinated, defecated, and ran around. The shocks continued. Eventually the frantic dogs would randomly scramble over a short barrier on one end of the room. Once over the barrier they were safe. After repeated exposure, the dogs in this group learned to bolt straight over the barrier to escape the shock.

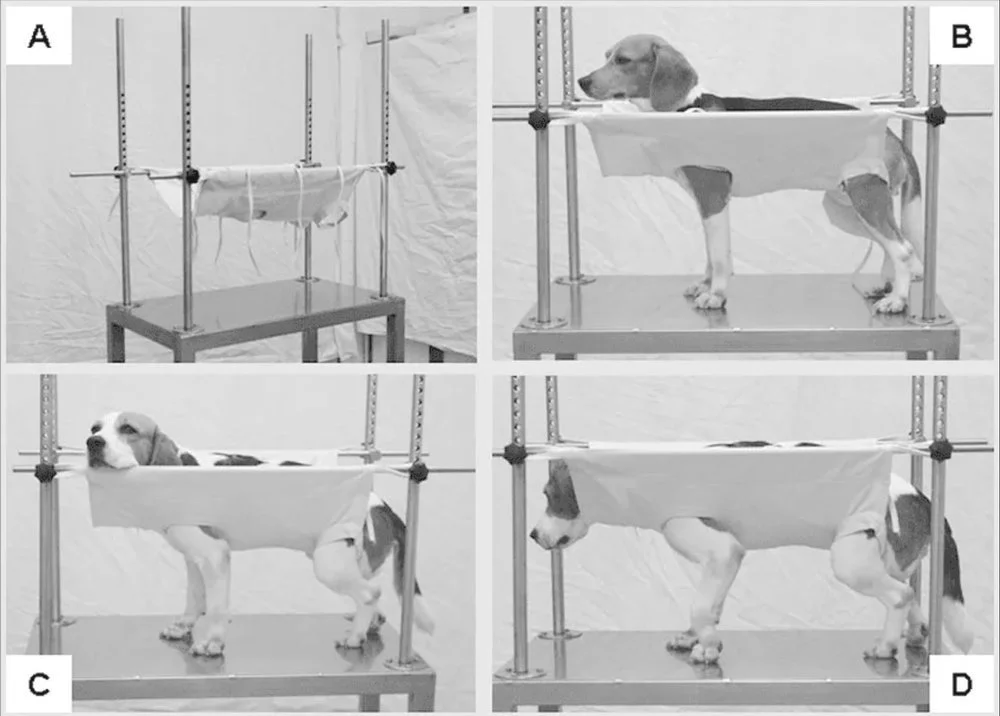

The lab then took another group of dogs and shocked them—with no recourse. Strapped into a “Pavlovian hammock,” a fabric harness, these dogs were given electric shocks they could not escape from. The shocks came and went and there was absolutely nothing the dogs could do to control them, until the time in the hammock was up. Seligman called this “Experience with uncontrollable trauma.”

These traumatized dogs were later put in the same experimental electro-floor chamber as the control group. At first, they behaved like the other dogs. They ran around and yelped. But not for long.

“A typical dog which has experienced uncontrollable shocks soon stops running and howling and sits or lies, quietly whining, until shock terminates,” describes the paper. “The dog does not cross the barrier and escape from shock. Rather, it seems to give up and passively accepts the shock. On succeeding trials, the dog continues to fail to make escape movements and takes as much shock as the experimenter chooses to give.”

PTSD dogs not only gave up. They also couldn’t learn.

Sometimes one of the dogs from this group was lucky enough to randomly run over the barrier and escape the shock. But a dog that did this didn’t realize it. The next time these dogs were placed in the electro-shock chamber, they “revert to taking the shock.”

Learned helplessness isn’t the result of anything these canines deserved. No one deserves trauma and shock, but we all receive it. How can we be more resilient?

Seligman's work led to the development of modern cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). CBT deemphasizes medication, instead teaching people with depression how to develop behaviors that help them feel better. One of the insights came when Seligman also worked with the dogs on a cure for helplessness.

Could researchers teach the helpless dogs to relearn agency?

Lab workers put the PTSD dogs back in the electro-shock room, and turned on the juice. The dogs cowered and whined as before. But then the handlers dragged the dogs by the leash across the room to the safe zone.

With repeated treatment like this, the dogs must have noticed three things.

One, they found that there was such a thing as safety.

Secondly, they started to notice the geography of safety.

Thirdly, they experienced moving to safety.

The handlers tried other methods to get the traumatized dogs to move themselves. They tried cajoling and scolding. They tried treats. Only one thing worked—physically moving the dogs’ bodies.

Every dog treated in this way recovered. They became able to run to safety on their own. “The recovery from helplessness is complete and lasting,” wrote Seligman, “and this finding has been replicated with over two dozen helpless dogs.”

The lab also developed a “vaccine.” The lab took a new group of dogs and shocked them in the electro-hammock. This time the dog learned that it could hit a paddle with its paw, and the shocks would end. Although the shock was no fun, they learned to look for a way to stop it.

Next, this group of dogs then got the traumatizing treatment—inescapable shocks in the electro-hammock.

Finally, when released into the electro-shock floor room that healthy dogs can escape from, what happened? They also learned how to escape, and about as quickly as the never-traumatized dogs.

“Experience in controlling trauma may protect organisms from the helplessness caused by inescapable trauma,” wrote Seligman.

Like puppy love, once you learn how to get yourself to safety, you can’t unlearn it.

***

Seligman’s paper draws connections to learned helplessness in humans and other species, including previous research in rats.

How long would you swim before drowning?

Did you know that a rat will swim for 60 hours before drowning? Two days, two nights, and another day.

But according to studies conducted before Seligman, if you squeeze a rat in your hands, it will struggle for a while, and then stop. If you then take a rat fresh from this brush with “uncontrollable trauma” and put it in the water, it will sink to the bottom and then drown within 30 minutes.

***

One more tidbit about the puppies that tells us a lot. Six out of 100 puppies walked into Seligman’s lab already as helpless as the dogs the lab traumatized. As he wrote, “Six percent of naive dogs are helpless without any prior experience with inescapable shock.”

Why?

Seligman doesn’t speculate, but I will. Even in a “good home,” a puppy could get scolded when it didn’t deserve it, or didn’t understand what it was being scolded for because the scolding was separated from the event. Even in a good home with enough food, a puppy could feel pressure at some point to compete with the litter for a treat. It could get squeezed out of the warm blanket and feel scared and out of control.

It’s easy to imagine 6% of puppies being exposed to “uncontrollable trauma” in the normal course of their puppyhood, even as their siblings weren’t. After all, it’s part of life.

Sincerely,

Tristan Roberts

Quill Nook Farm