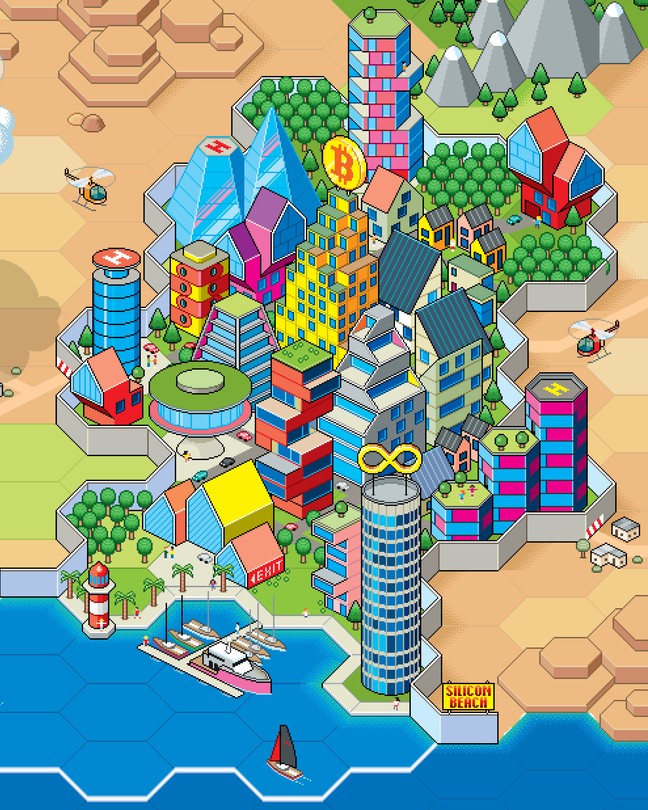

Meet Me in the Eternal City

Silicon Valley has always dreamed of building its own utopias. Who’s ready to move in?

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

I.

The international airport serving the capital of Montenegro has only two arrival gates, and last spring they were busier than usual. I was there for the same reason many others were: The tiny Balkan state had become the unlikely center of a mostly American social and political movement.

Specifically, I had come to observe Zuzalu, a two-month co-living experiment that had been organized—and to some extent paid for—by Vitalik Buterin, a co-founder of the eco-friendly cryptocurrency ethereum. It was being hosted at a new resort and planned community on the Adriatic coast, not far from the village of Radovići. Part retreat and part conference, it was also a dry run for the more permanent relocation of tech-industry digital nomads to different parts of the world, where they could start their own societies and design them to their liking. Some 200 people had signed up for the full two months. Others, like me, popped in and out. The slate of talks for the days I was there was titled “New Cities and Network States.” European tourists smoked cigars on the promenade while Zuzalu attendees bounded around making plans for excursions and exercise and shuttles to a private Grimes show later on.

The network state is a concept first advanced by Balaji Srinivasan, a bitcoin advocate who is influential in tech circles. As he describes it in his book, The Network State, self-published in 2022 on the Fourth of July, a network state starts with an online community of like-minded people, then moves into the offline world by crowdfunding the purchase of land and inhabiting it intensively enough that “at least one pre-existing government” is moved to offer diplomatic recognition. There isn’t necessarily any voting; the best way to vote is by either staying put or “exiting” for another network state you like better.

Other than that, the model is choose your own adventure. Hypothetically, Srinivasan suggests network states for people who eat specific diets (kosher, keto), for people who don’t like FDA regulation, for people who don’t like cancel culture, for people who want to live like Benedictine monks, for people who might want to limit internet use by putting public buildings in Faraday cages. It doesn’t matter what the state is based on, but it has to be based on something—a “moral innovation” or a “one commandment.”

So, in Montenegro, inside a geodesic dome, presenters gave pitches for an array of proposed societies. The talks were of the friendly “no bad ideas in brainstorming” variety—propositions with enormous stakes presented one after another in an hour or less. Beginning as online communities, or as “decentralized autonomous organizations,” some would be built from scratch by people with a shared cause. Others would be start-ups in a more traditional sense—instigated by founders and run like businesses. For instance, Titus Gebel, a German entrepreneur, proposes the establishment of “free private cities,” where citizens are customers who pay only for the government services they intend to use personally. A city operator and a small governing board would make every important decision. “The current Western legacy systems are not reformable,” Gebel said during a presentation. “They’re not really serving people’s needs any longer.”

Later, I listened to a Q&A with Dryden Brown, the 20-something CEO and co-founder of Praxis, a venture-capital-funded group bent on escaping American democracy and all its flaws by building a new “eternal city,” also called Praxis, somewhere in the Mediterranean region. On the internet, Brown is combative and self-aggrandizing, but in person, he has the reflexive politeness of someone who is used to older adults referring to him as a “nice young man.” When he was in his early 20s, he posted a meme on Facebook identifying himself as “fiscally conservative and socially awkward.” He’d been avoiding me in New York, but when I appeared in Montenegro, he received me with surprising warmth (“You made it!” he said, after I sneaked into the Grimes show).

During his Q&A, he stuck mostly to oft-repeated talking points. His family fought in the Revolutionary War; he has wanted to start a new city since he was 15 or 16 years old; the important thing to know about Praxis is that everyone who lives there will be amazing. “If you’re able to get the next Elon to move to the city, that’s where the returns come from,” he said. Brown acknowledged the need to “attract and retain people who have that risk tolerance, that are talented, that have that high IQ.” He said the “high IQ” part twice.

On the second day of presentations, I had lunch with a biotech investor named Sebastian Brunemeier. (But he was fasting, so we only drank water.) Brunemeier, remarkably friendly and forthcoming, is a “longevity maximalist” who co-founded a venture-capital fund in 2021 to invest in something called LongBio. Now, he explained, he’s supporting a longevity-specific network state that would advance a cause he and others call “vitalism.” Death, they argue, is an option, not an inevitability. “The basic premise is: Well, if life is good and health is good, death and disease are bad,” Brunemeier explained. Citizens of this network state will be free to pursue a goal of longer, healthier lives outside the reach of U.S. regulation and its byzantine restrictions on medical experimentation. (Outside the reach of the U.S. tax code, too.) To start, they’re hosting a two-month pop-up city called Vitalia on an island off Honduras.

A smattering of other network-state-inspired projects are under way. There’s Itana, a new city in Nigeria marketed to entrepreneurs, which entices foreign business owners with tax incentives. The island off Honduras where the vitalism people are headed is home to an existing community called Próspera, whose settlers are already offering experimental gene therapy. The venture capitalist Shervin Pishevar, a co-founder of Hyperloop One, is building what he calls a “smart island,” in the Bahamas. So far it sounds like a planned community with its own airport, but Pishevar has promised that his ambitions are much larger. “One of our next projects is an island that is bigger than Manhattan,” he said at a Srinivasan-led network-state conference in Amsterdam this past October. He didn’t name the location, but said he is negotiating a “treaty, essentially,” a 99-year lease with a host government.

These projects are pitched with a sense of grandiosity and grievance: The twisted bureaucracy of democratic governance is constraining humanity. Decades ago, we went to the moon; why don’t we have flying cars? Centuries ago, we praised frontiersmen and pioneers; why are they vilified now? Why all this disdain for the doers and the builders? Why all this red tape in the way of the best and the brightest?

Most of these projects are not yet real to the point of treaties and cement, but they are real enough in the minds of people who wield influence in a powerful, tight-knit industry. These people are energetic, creative, and sometimes charming. And they have their hearts set on a future that belongs to them alone.

II.

The idea of the network state is not a totally original one. The United States has a long history of secessionist yearning, and the specific dream of libertarian settlements populated by Americans has been in the air since at least the 1970s, when the reactionary Nevada millionaire Michael Oliver determined that “the real cure for this country is for the productive people to leave, and let the moochers tax each other.” As recounted in Raymond B. Craib’s recent book, Adventure Capitalism, Oliver first thought of building an artificial island in the South Pacific; his later schemes included invading some islands in the Bahamas and funding a right-wing separatist movement in Portugal.

The network-state idea also sounds a lot like the Patchwork concept proposed 15 years ago by Curtis Yarvin, a tech-world personality who is regarded as the father of neo-reactionary thought. In 2008, on his blog Unqualified Reservations, he wrote:

The basic idea of Patchwork is that, as the crappy governments we inherited from history are smashed, they should be replaced by a global spiderweb of tens, even hundreds, of thousands of sovereign and independent mini-countries, each governed by its own joint-stock corporation without regard to the residents’ opinions. If residents don’t like their government, they can and should move.

Like much of Yarvin’s writing, this post was heavily sarcastic and full of what one would hope is hyperbole. To rid San Francisco of the poor, he suggested “a little aerial bombing.” His tone could be why the idea languished for so long; that, and some of the things you’ll find in his Wikipedia entry under the headings “Alt-right” and “Views on Race.” Now, however, people who are tired of the messy reality of the United States are returning to Yarvin’s work with fresh appreciation. “He was just so early,” William Ball, a co-founder of the venture-capital firm Assembly Capital, said in a podcast interview.

In hindsight, the network state is clearly the dream that Silicon Valley has been building toward since the very beginning. In a famous 1995 essay, “The Californian Ideology,” the British academics Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron explained that the technologists of Silicon Valley looked forward to a future in which “existing social, political, and legal power structures will wither away to be replaced by unfettered interactions between autonomous individuals and their software.” The authors also observed, dryly, that California’s highways, universities, and extensive public infrastructure had all been built by complex bureaucracies and funded by taxes.

Two years later, the tech world produced its own version of the same thesis, without the analytical distance. The Sovereign Individual, by the American investor James Dale Davidson and the British journalist Lord William Rees-Mogg, was published just as the tech industry in California was rising to power. It was a manifesto for the concept of “self-ownership,” and displayed utter disdain for any kind of reciprocal relationship with government. Davidson and Rees-Mogg at times make their case with metaphors so distracting that the impact is somewhat muted. (“The state has grown used to treating its taxpayers as a farmer treats his cows, keeping them in a field to be milked. Soon, the cow will have wings.”) But the book is still read today—Peter Thiel wrote a new introduction for a 2020 reprint—because it predicted the development of cryptocurrency. It also predicted that, as nation-states became unwieldy, the most stable mode of government might become the city-state—“the old Venetian model.”

In this new age, computers would alter every institution, the very structure of society, and the entire world economy. In doing so, they would imperil national governments by curtailing their power to control citizens and collect taxes. They would also create a permanently wealthy superior class, a “cognitive elite,” whose members may exist “in the same physical environment as the ordinary, subject citizen” but who would never again regard ordinary citizens as their equals.

Eventually, this elite would move, frictionlessly, all over the globe. As participants in a new, totally online economy, they could break free from the “tyranny of place” and go wherever they wished, pursuing maximum freedom and paying what they liked for commercialized versions of the services previously provided by the state. Objecting to any of this on moral grounds, Davidson and Rees-Mogg insinuated, was the province of Luddites and deluded nationalists.

Silicon Valley’s fixation on “exit” was arguably most visible (and most derided) in the late aughts and early 2010s, when Patri Friedman (the grandson of the free-market theorist Milton Friedman) and Thiel were working on the Seasteading Institute and hoping to build “floating cities” on the open ocean. That project, mocked as “Burning Man on the High Seas,” was doomed by its technical difficulty and inherent goofiness. When I spoke with Friedman on Zoom last summer, he was wearing a glittery pair of kitten ears and talked animatedly about what he saw as a moment of opportunity. Friedman’s investment fund, Pronomos Capital, is backed by Thiel and has money in projects on five continents. (It has helped fund Praxis, Próspera, and Itana, among other network-state ventures.) Friedman has been touting the idea of “competitive governance”—treating government like an industry, which can be disrupted by start-ups—for 20 years. “People take it much more seriously now,” he said.

The Network State was instantly popular among Silicon Valley thought leaders. It was endorsed by the investor Marc Andreessen, the Coinbase CEO and co-founder Brian Armstrong, and the AngelList co-founder Naval Ravikant, among others. Maybe most important, it was endorsed by Vitalik Buterin, who published a blog post taking issue with some of Srinivasan’s points but ultimately championing his basic premise.

Buterin and Srinivasan make for a contrast. Srinivasan is a brash Indian American who is all-in on bitcoin, the clunkier cryptocurrency with a notoriously bro-y, right-wing reputation. He fights with people on social media and refers to journalists as “dogs on a leash.” Buterin is younger, a Russian Canadian with an elfin look. He comes off as softer and kinder, and his cryptocurrency, ethereum, is favored by projects all across the political spectrum, including many on the far left. People who might shy away from a movement spearheaded by Srinivasan alone would feel comforted by Buterin’s participation, and vice versa. His biggest quibbles with Srinivasan’s concept, as originally written, were that network states could easily wind up as havens for the wealthy and that an all-powerful founder should be a temporary step, not a permanent condition. “Network states, with some modifications that push for more democratic governance and positive relationships with the communities that surround them, plus some other way to help everyone else? That is a vision that I can get behind,” Buterin concluded.

With that more expansive definition, the idea has some broad appeal. As you’ve heard, the pandemic accelerated the movement of various aspects of life onto the internet. It is more common than ever to identify as a digital nomad or a remote worker—to take your American salary and move somewhere with a lower cost of living, to bop around wherever you want. It may also be more common than ever to feel like something about America is fundamentally wrong—that it’s on the brink of one or multiple crises that can’t or won’t be avoided.

Most network-state advocates try to avoid talking too much or too negatively about the people and societies they’d like to leave behind. Still, it’s hard not to hear an undertone of bitterness when they do. Srinivasan’s book is as much about the culture war as it is about utopia-building. He argues that a “blue tribe” of “left-authoritarians” currently holds most of the power in the United States. For years, Srinivasan argues, this liberal cabal has been canceling, deplatforming, demonizing, and dominating. The time has come to “reopen” the frontier. It’s a tale as old as civilization: When you’re persecuted, you get out of town.

III.

Praxis first caught my attention because of its presence in New York City’s downtown. I had wandered into one of its parties out of curiosity. With roughly $19 million in venture-capital funding—from sources including the Winklevoss twins (of Facebook fame); a fund run by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and his brother Jack; a couple of crypto funds that recently collapsed in spectacular fashion; and industry heavyweights such as Paradigm and Bedrock Capital—the Praxis people had been throwing parties for years before Zuzalu. Models and artists and musicians and other cool kids were invited and given dog tags to wear, reading Meet Me in the Eternal City.

“The way you get people interested in this stuff is by making it culturally interesting,” Riva Tez, a venture capitalist and an Ayn Rand devotee, explained in a 2022 interview about her early investment in Praxis. “How do we build the Galt’s Gulch for the next generation?” she asked, referring to the secluded libertarian society built by disillusioned industrialists in Atlas Shrugged. “It’s got to seem fun. It’s got to seem like people you want to go join.” To this end, Praxis has been wriggling its way into the seductive counterculture, born on the internet, that has coalesced in recent years to mock what it sees as the Millennial-liberal mainstream; a counterculture that flirts with some fairly right-wing talking points on racial politics and gender roles, among other things. Usually, participants in this scene maintain a playful level of plausible deniability, but not always. During a gathering last summer in its SoHo office, would-be future residents of Praxis split into groups to tackle various big questions, including this one asked by an attendee: “In an ideal society, to what extent should women be working or go to college or be trained the same as men?”

The best marketing for a new city is the troubled condition of the ones we already have. Last year, when distant wildfires turned the sky orange, and the news was saying that being outside in New York City for a day was the equivalent of smoking six cigarettes, Praxis hosted a weeklong series of parties throughout Manhattan, including a black-tie gala. Afterward, I wrote to Olivia Kan-Sperling, a New York art-world figure and novelist whom I’d seen at one of the parties, and who had written an article for Praxis’s online journal. I asked whether we could meet to talk about Praxis. She wrote back that she didn’t know much, but doubted the motives of people—I had a feeling she was including me—who would reflexively dismiss it. “I find it interesting that critics of the project seem to have no problem living in a city where homeless people are allowed to die on their doorsteps, in a country that murders people at home and abroad every day.”

A central premise of Praxis—paradoxically, for a project built on shoot-for-the-moon wild-wishing—is that we have limited options if we dislike the way things currently stand. The problems in, say, New York are obviously the result of untold years of human failure and bureaucratic dysfunction. So what would you rather do if these are your only two choices: Try to accrue the political power to pull on just one tiny thread, or start over with absolute control?

Not long after the parties in the wildfire smoke, Dryden Brown posted in the Praxis Telegram chat that he would be on a plane for a few hours and would answer any questions the community had. He responded to the first several, explaining that Praxis would be governed by a “zone operator” (presumably himself), that he would like for the city to use nuclear and maybe geothermal energy, and that his favorite forms of transportation are walking and driving. Then the questions got harder. What kinds of industries would Praxis be supporting, and what kinds of regulatory concessions from the host country would it need? Who would do the farming, plumbing, and other “difficult specialized labor” in Praxis? How would “our ‘different’ view on democracy” read to Europeans? Brown didn’t answer these last few questions.

He barely responded to a Mother Jones report, published in September, in which former Praxis employees said that he had white-supremacist and fascist leanings, expressed in casual conversation and evident in the reading lists he had given to new hires. (“We won’t let gossip stop us,” Brown said in a statement to Mother Jones at the time; he more recently characterized the claims in that article as “false” and “unsubstantiated,” and added that Praxis had “never promoted” any far-right talking points.) In late October, Brown announced that he had gotten an offer from a country that would give him land, infrastructure, and a “regulatory sandbox” in exchange for some kind of equity in his project. He is now offering a silver membership card he calls a Steel Visa—“your entry point to the Praxis community”—and posting mock-ups of postage stamps (which depict men in suits of armor). In 2026, he says, you’ll be able to live and work, legally, in whichever mystery country will be home to Praxis. (Brown is also partnering with a start-up that says it can help him control the weather.)

By my count, Galt’s Gulch had an identifiable population of about 25, including two women, one an unnamed “fishwife,” considered to be a stand-in for Rand herself. It wasn’t even a town. In the book, it’s described as “a cluster of houses scattered at random.” Everybody who lives there has exactly the same views about life and industry, and about their responsibilities to one another, which are zero. Residents were selected to maintain the settlement’s ideological purity. This is, of course, radically anti-American, in the sense that the American project has been to allow different constituencies and interests to coexist and share power (and responsibility), however imperfectly. Galt’s Gulch residents were required to take an oath: “I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.”

This is one model for something like Praxis. Brown has said that the residents will be like-minded. They will have to apply for the right to become residents and to buy property. As he once explained, “If you live in a society with people who have radically different, really foundational values, they’re not able to architect a harmonious path toward a better future, because they disagree as to what a better future is.”

IV.

Montenegro’s government seems to be amenable to network-state projects, which is why both Praxis and Vitalia have considered it as a building site. The country launched a visa program for digital nomads in 2021 and granted Vitalik Buterin citizenship in 2022. There has been talk of creating further incentives to lure in Silicon Valley defectors, possibly by creating a digital currency backed by the country’s central bank. But this is all politically fragile. The country’s prime minister—who made an appearance at Zuzalu—has been subject to insinuations of corruption because of alleged coziness with the crypto industry. No potential host country offers a truly blank slate.

That was a point made by Patrick Lamson-Hall, an urban planner who was at Zuzalu to give the “straight man” presentation, as he put it, about how cities really work. He was there only for the weekend. (“I’m, like, a normal person,” he said, when I asked if he’d be staying for the full two-month experiment.) Over breakfast one morning, Lamson-Hall brought up the glamorous Próspera settlement in Honduras, which was built as a sort of enhanced special economic zone with all kinds of jurisdictional powers. The government that had signed off on this deal had recently been voted out, in favor of a new regime that had campaigned specifically on a platform of rescinding such privileges. Now the Delaware-based corporation behind the project was suing the Honduran government for more than $10 billion, roughly two-thirds of the country’s total annual budget. “They ran ahead of the will of the people,” Lamson-Hall observed. Who’s to say the same thing won’t happen in Montenegro? Or Palau? Or Costa Rica or Nigeria or any of the other places where plans are being hatched?

He wasn’t opposed to the general premise of new urban centers, and said he applauded the ambition he’d seen on display at Zuzalu. He liked some of these network-state people, and he liked that they wanted to test new solutions. Nevertheless, he added, as he cut into an elaborate meat pastry, “in practice, I think it would be a dystopian nightmare.”

The whole point of network states is to discard messy processes, he said. That seems expedient on its face but is actually shortsighted. Even if you manage to get your way, you can’t control how people will then react to what you’ve done. “Development stems from consensus within society,” he said. You have to tolerate plodding. “You aren’t always going to get there the fastest, but when you get there, you’re there.” The young people at Zuzalu, in his opinion, were moving too fast to even consider their own future thoroughly—they weren’t building as if they might someday have families, or might age, or might desire a different lifestyle than that of gourmet meals and high-end recreation in a secluded coastal paradise. “They can’t really imagine their own preferences might change.”

Lamson-Hall gestured around at the resort and the hundreds of apartment-villas behind it, which he took to be a good model of what a lot of these network-state projects could look like. “This is a Potemkin city. You couldn’t have a business. You couldn’t get your car fixed.” The locals change bedsheets and make coffee and speak passable English. What would the network state offer them? Maybe some jobs; possibly designation as a permanent underclass. Though most of the network-state pioneers talk about the value they’ll provide to local economies, they haven’t thought much about the details, if at all.

“I’m not a class warrior by any means,” Lamson-Hall emphasized. But he was struck by the elitism of some of the presenters at Zuzalu. Many of them seemed to want to avoid responsibility for other people. More than that, they seemed offended by the idea that anyone would even ask them to bear that responsibility. “People with that mindset having the powers of a sovereign state, which are considerable, really freaks me out,” he said.

V.

At Zuzalu, there seemed to be consensus among presenters that American cities had created enormous cultural value, but were now outdated and horribly mismanaged. “I don’t know anybody who lives in New York City for the governance,” Colin O’Donnell, the founder of a “van life” network project called Kift, observed. That’s true, I thought at the time. I hate our mayor. But I now realize it wasn’t true, really. I live in New York because I couldn’t stand to live anywhere else and because I’m in awe of the puzzle: It doesn’t work well … but how does it work as well as it does?

When I got back from Montenegro, I had a birthday party to go to in Queens, but I was early, so I sat in Flushing Meadows Corona Park to watch the neighborhood men play soccer. This park was once a salt marsh. Then it was a trash heap, 30 feet high in most places. The mixture of wet coal debris and street sweepings attracted rats, mosquitoes, and a famous Long Island alcoholic, F. Scott Fitzgerald, who in The Great Gatsby described the mess as “a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens.” It’s thanks to a dysfunctional bureaucracy that the trash heap became a park with 100 soccer teams playing in it every weekend. The polarizing city planner Robert Moses commissioned the park’s 140-foot-tall Unisphere, the unofficial Statue of Liberty of Queens: a big steel sculpture of the Earth that people hated when it was built. It was corporate crap—uninspired, trite, reminiscent of “an ad for Western Union,” as Newsday put it. In his 1978 book, Delirious New York, the architect Rem Koolhaas wrote that the metal continents hung off the globe’s skeleton “like charred pork chops.” Yeah, but on a day when the sky is very blue?

A recent report found that half of working-age New Yorkers, almost 3 million people, can’t afford to live here. Yet they do live here. The city, with all its complexities and cruelties, is rife with small miracles. Like 100 soccer teams on a weekend. Or the fact that, in 1964, Michelangelo’s Pietà was exhibited in this park, and the people who couldn’t afford to live here lined up to look at it and weep. On this day, teenagers were standing around and flirting before the Mets game. The public golf course would be open until one in the morning. The subways would run all night. While I sat there, families passed around pieces of barbecued chicken and birthday cake. Old men sat on the sidelines and drank Gatorade. This park may be underwater in my lifetime, people say, possibly by 2050, when I will be just 57 years old. Someone promises you an eternal city? Nothing is eternal.

Nothing is perfect, either. No city, and no life led in one. No matter how meticulously planned or sumptuously mocked-up, any utopian enclave will become a stage for human drama that nobody can script or predict. Suddenly, I thought of the question that I’d been neglecting to pose to every one of these people, which had been lingering at the back of my mind. I wanted to ask: “Have you ever heard the expression ‘Wherever you go, there you are’?”

This article appears in the March 2024 print edition with the headline “Meet Me in the Eternal City.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.